Stickpin Revolution

Assisting in estate liquidation with consignment is something we do often at Grandview Mercantile. We love being able to help folks rehome their treasures in times of transition. While we don’t typically take entire collections because of the time involved to treat them properly, this collection was simply too marvelous to pass by.

Displayed in spool and map cabinets, the collection arrived to us just as it was in The Collector’s home. We were in awe of the magnitude, of the thoughtful organization, of the whimsy.

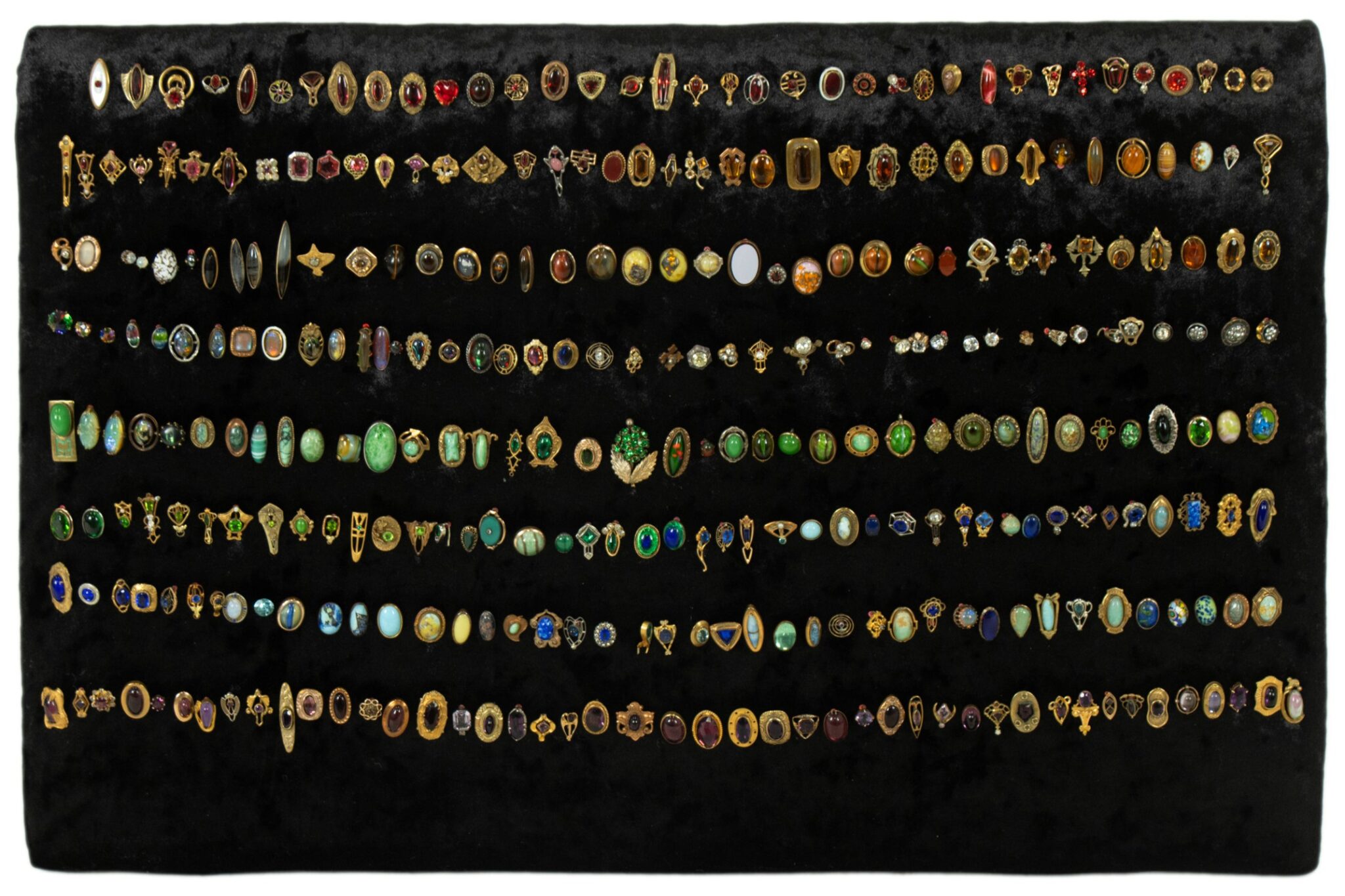

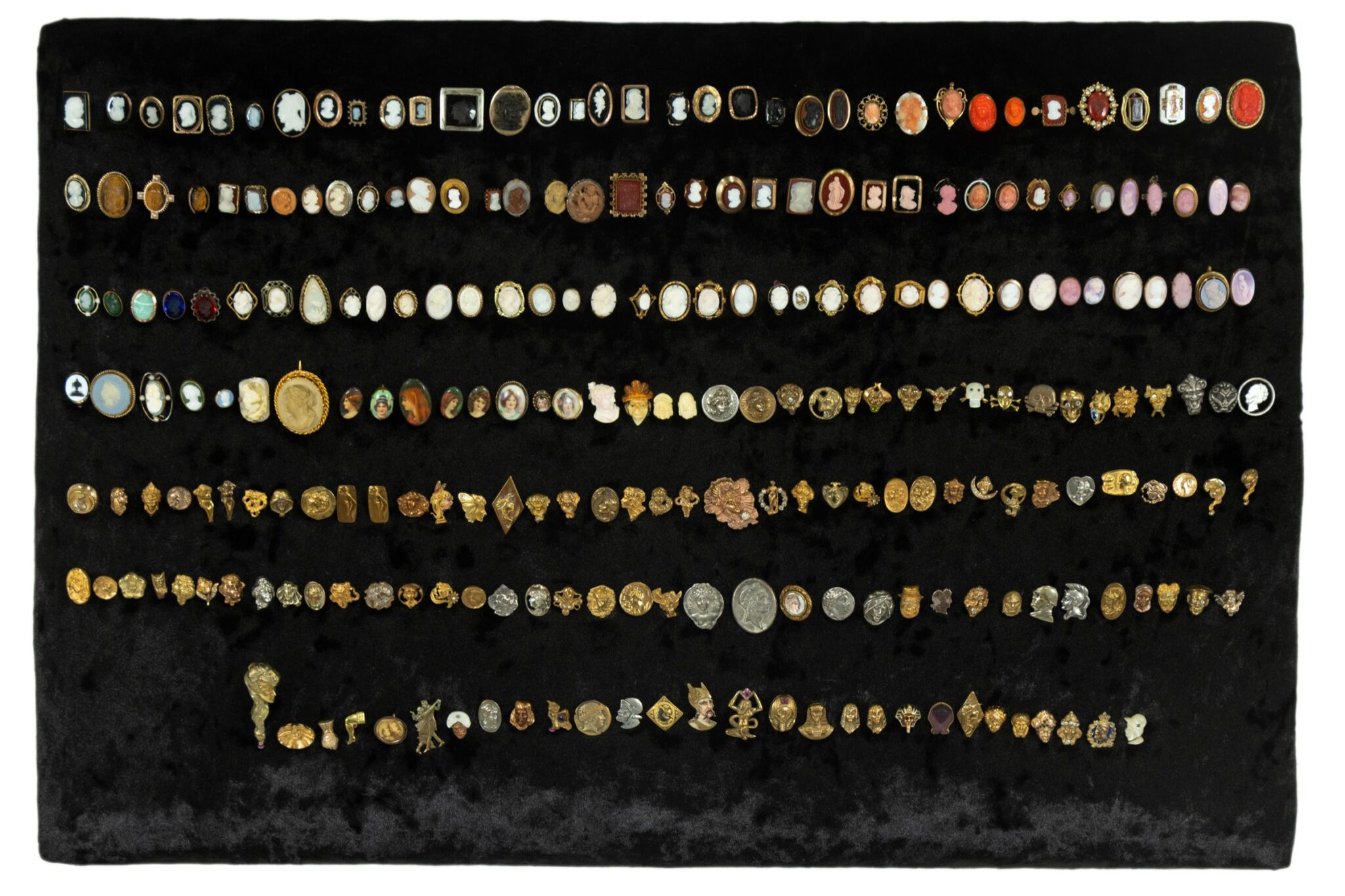

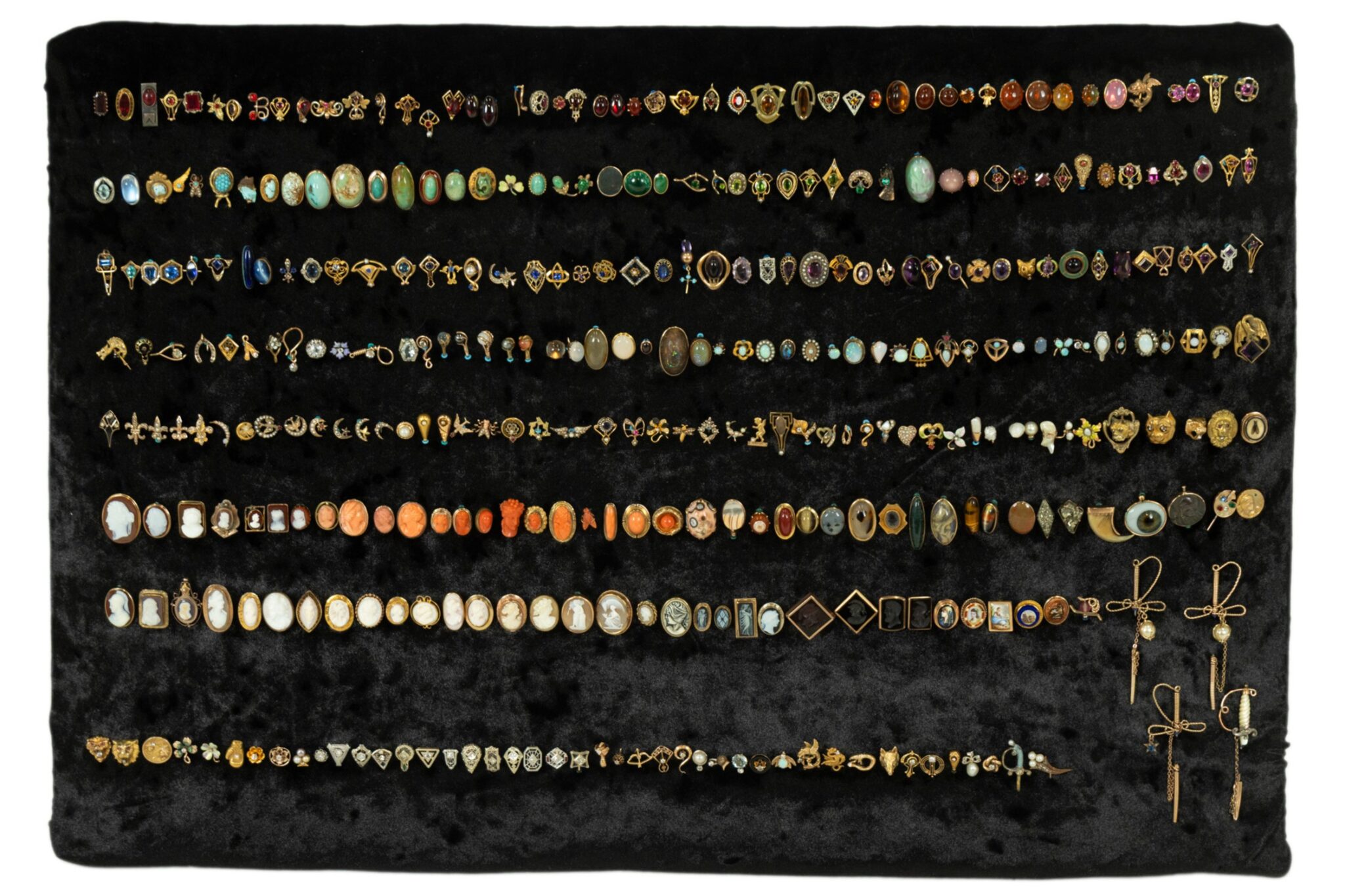

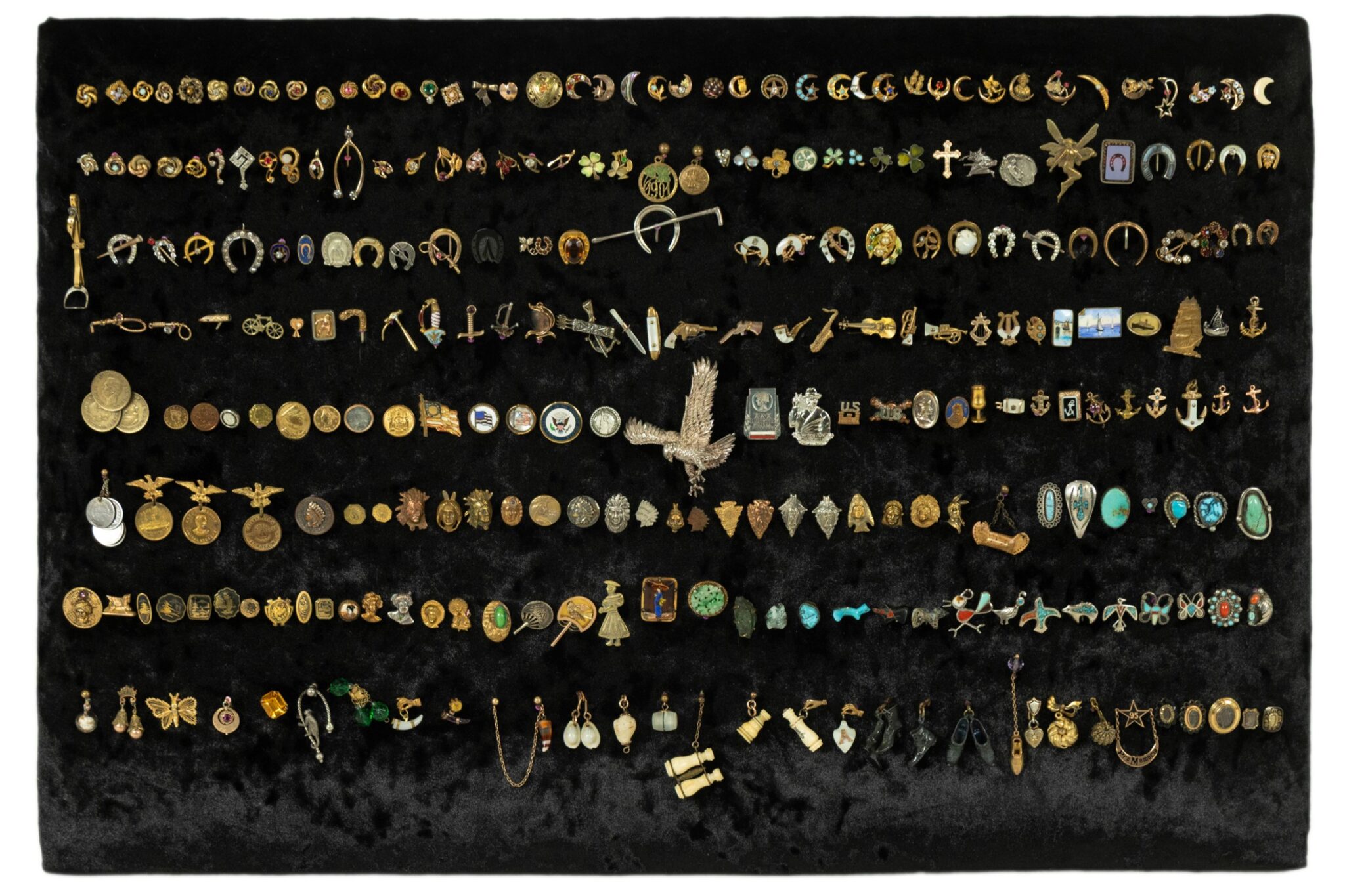

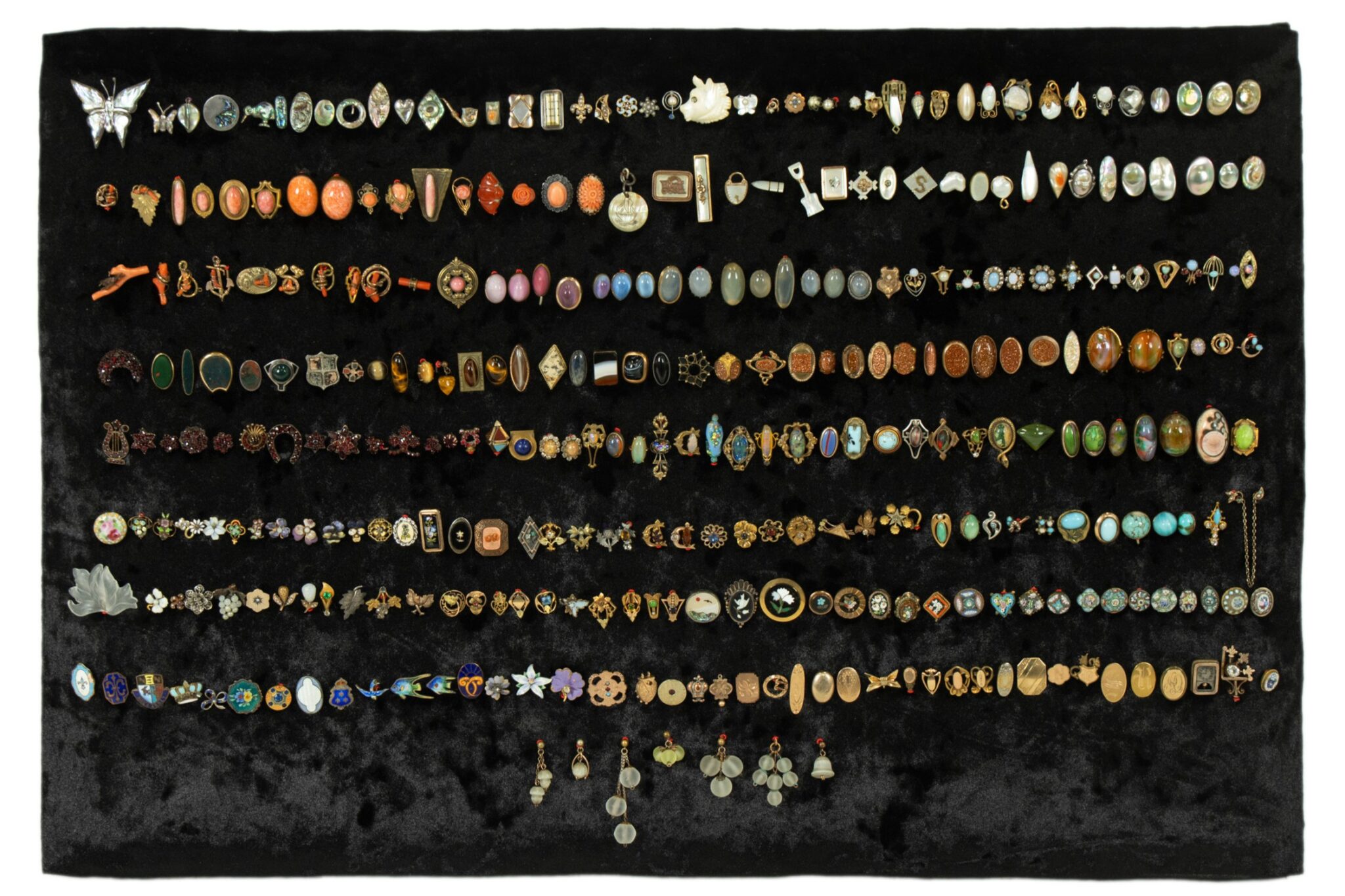

It took us months to process– each pin was tested for gems and gold, and was separated into categories. We purchased a custom display case that was brought in on consignment. We added custom lighting to make sure the details of each pin can be seen and appreciated. We created custom display panels so they could be shown on cushioned black velvet. We researched, we delighted, and we stuck ourselves with the pointy ends many times over. We marked each pin with a color coded band, and stuck each one individually into those display panels. All said, they totaled upwards of 1,700 individual stickpins.

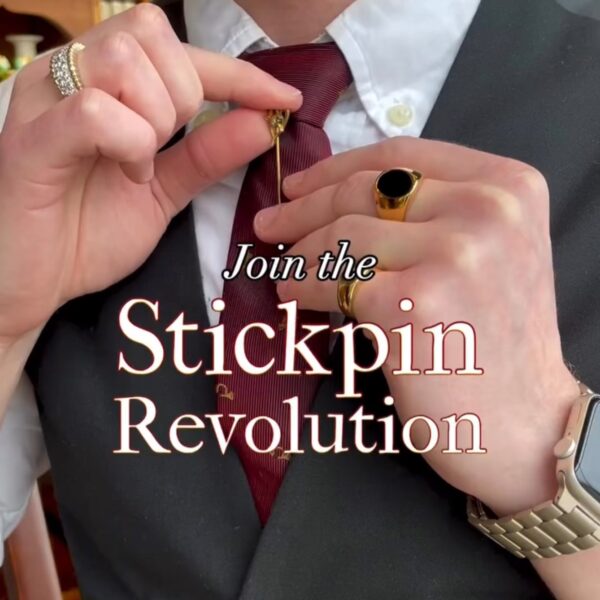

At long last, we are ready to show this collection off, and demonstrate how stickpins can be a revolutionary addition to your own wardrobe and collection.

The Collector’s interest in stickpins began in the early 1980s. She and her husband would travel to antique malls and markets all over Ohio in the pursuit of treasure, not picking up more than a few at a time. In the late 1980s, her husband refinished and outfitted a map cabinet and a spool cabinet with padded velvet inserts to properly store and display her collection. This only motivated her to collect further!

Her husband passed away in 2005, and that is when her collecting ceased. All said, her collecting spanned 25-30 years. The collection was lovingly built up over years of purposeful treasure hunting. She collected these stickpins because they were interesting and fun to look at, not because they were exceptionally valuable. They were small joys in life that she cherished.

We hope to honor the memory of The Collector by getting this fabulous collection into the hands of people who will love them like she did. The Collector is the inspiration behind the Stickpin Revolution.

Stickpins are defined by two parts: the decorative head, and the straight, functional pin. The execution of these two elements varies by era and manufacturer. Some pins can have a twist to help keep secure in a cravat. They were largely produced between 1830 and 1920, with some modern and contemporary reproductions.

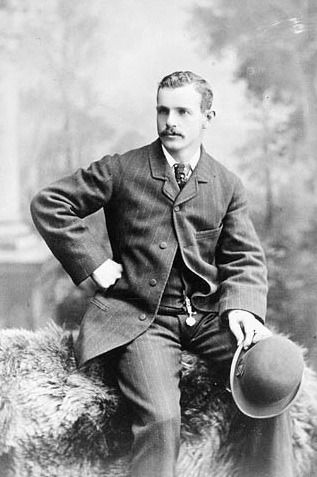

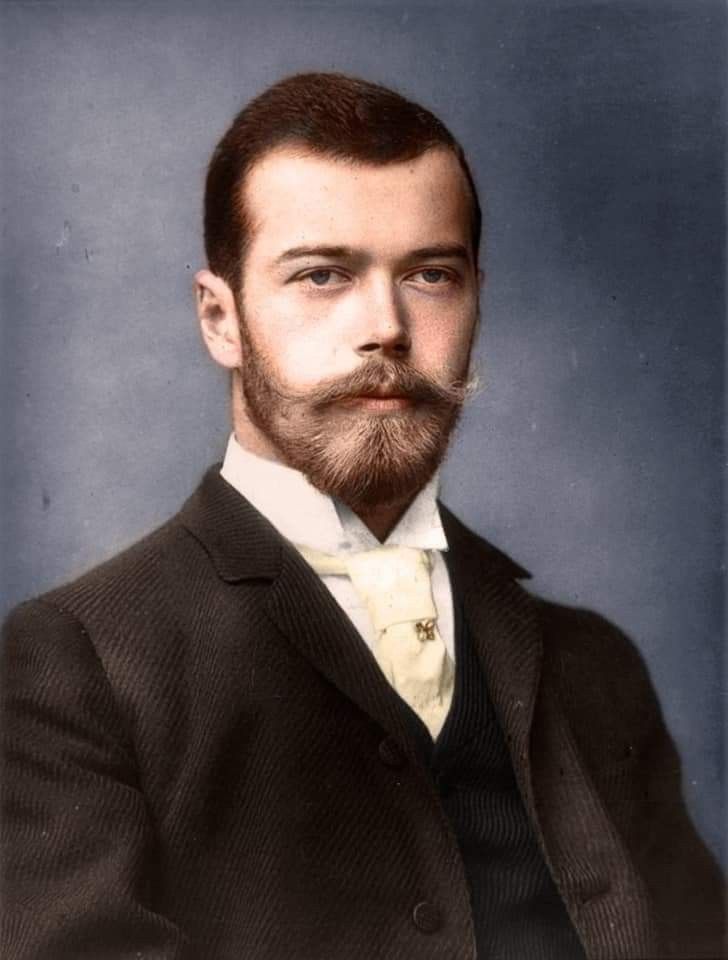

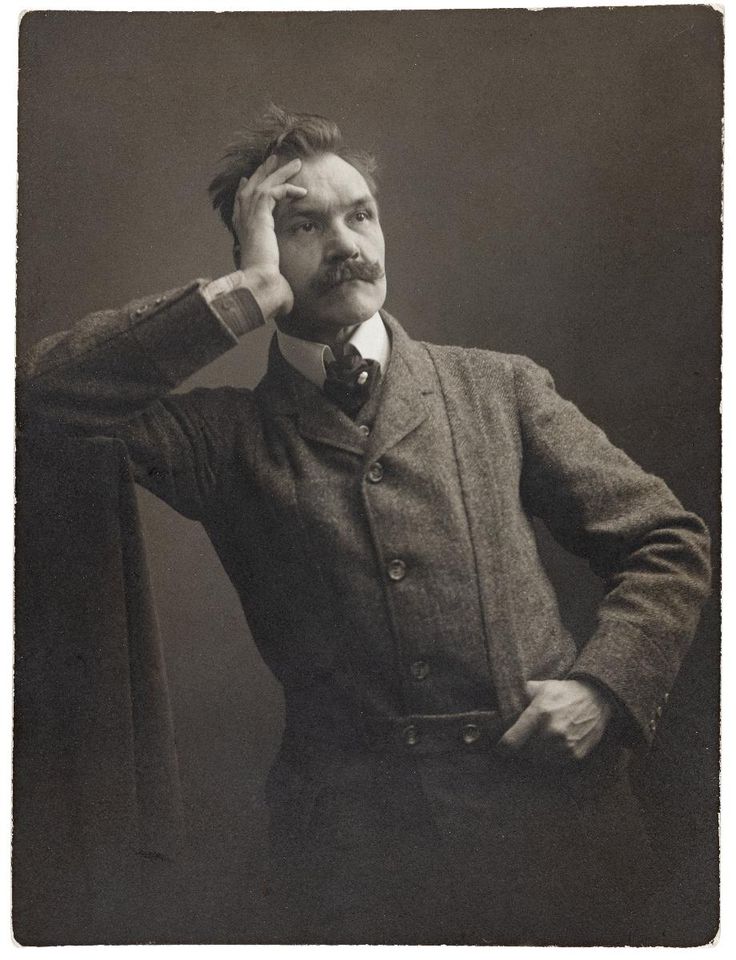

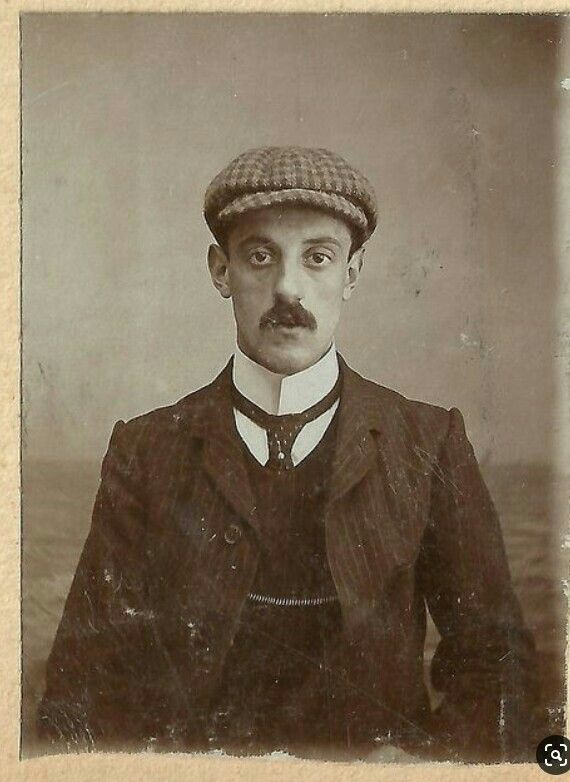

As seen on the HBO hit The Gilded Age by Julian Fellowes, set in the 1880s. Nearly every gentleman wears one!

Stickpins are the perfect way to add a bit of vintage flair to your wardrobe! With heads the average size of a fingertip, they can be added to just about any item of clothing!

- Hats

- Beret

- Beanie

- Sun hat

- Wide brim hat

- Cowboy hats

- Sweaters

- Along the trim of a cardigan

- At the neck of a crew neck

- At the top of a turtleneck

- At the base of a V-neck

- Spice up a plain tee

- V-neck, crew neck, mock neck, turtle neck

- Button downs

- From dress shirts to flannel

- Along the lapel

- Clustered on the chest

- Accenting a pocket

- Fitted over a button

- Jackets

- Jean jackets

- Blazer lapel

- Bomber jacket

- Scarves and Ties

- Ascot or cravat

- Silk or crocheted neck scarf

- Long silk scarf

- Light and flowy shawl

- Winter scarf

- Wide or thin tie

- Bow tie

- Skirts and dresses

- Along the neckline of any dress

- Pinning an oversized dress at the waist for a more defined look

- Pin up the corner of a skirt

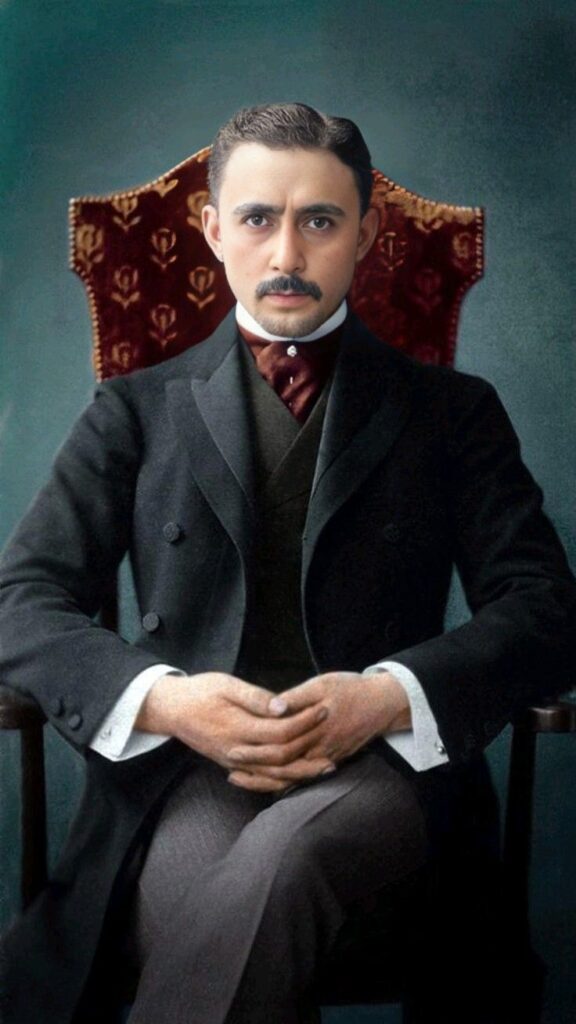

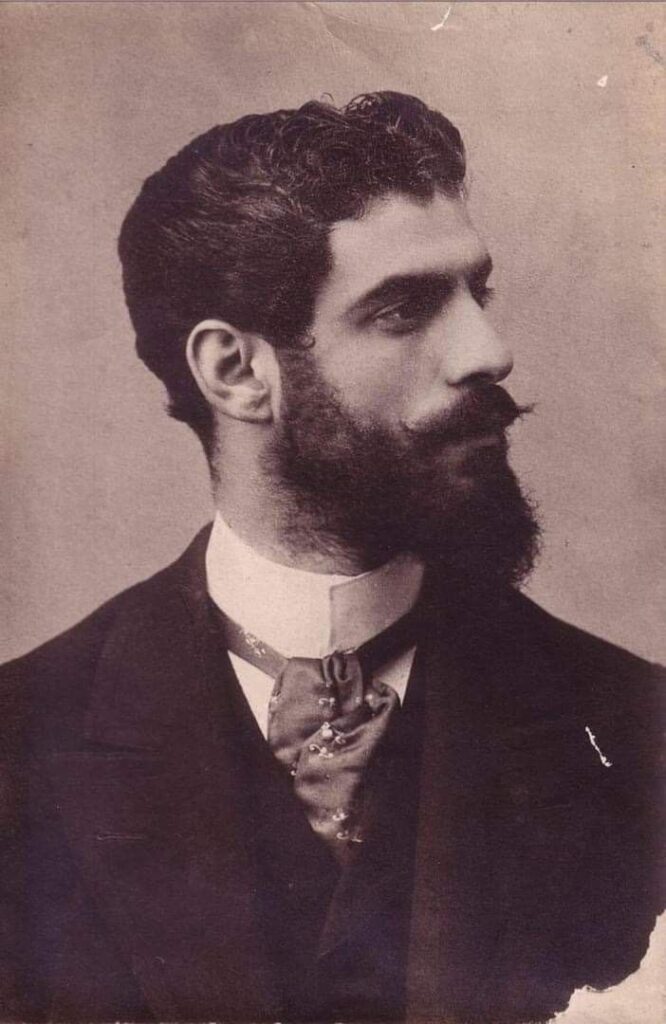

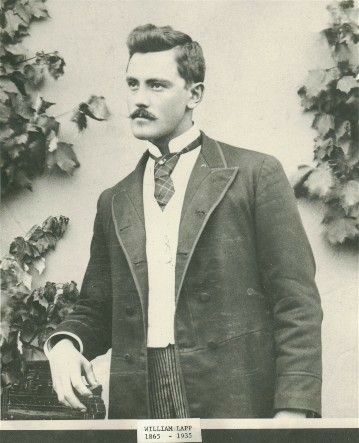

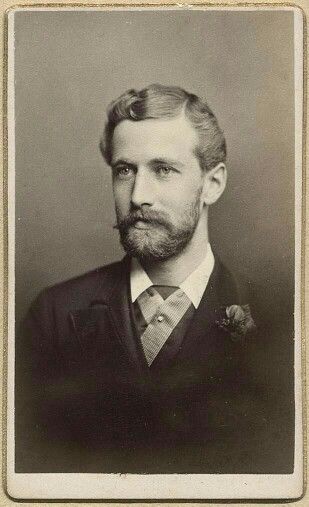

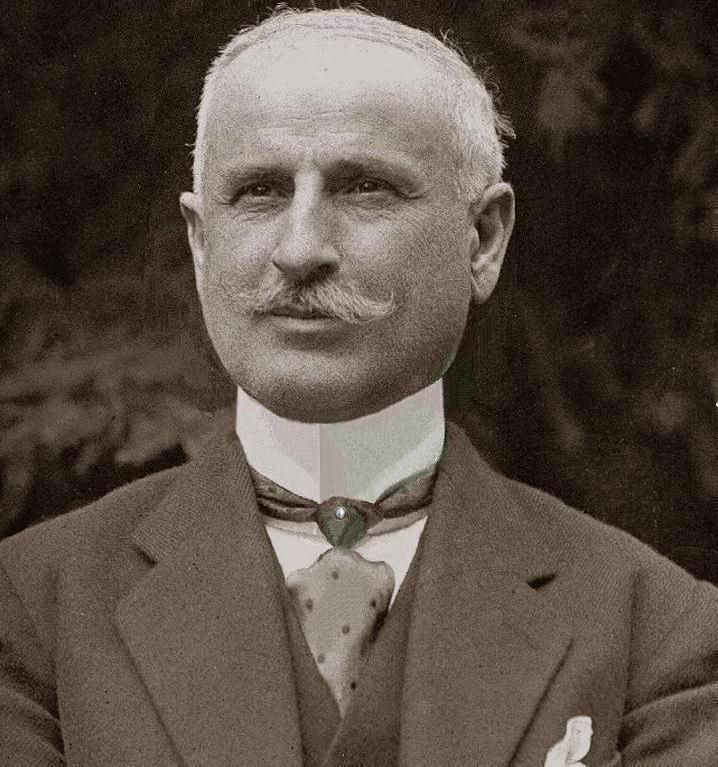

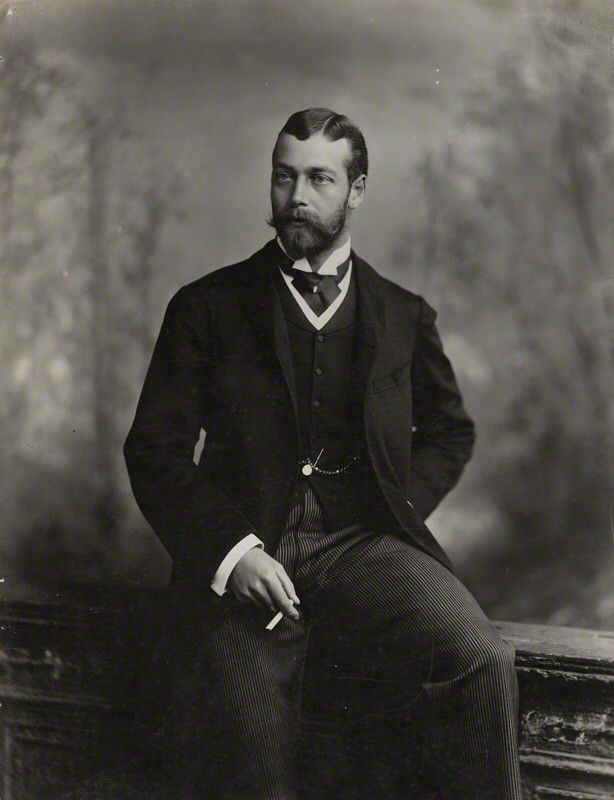

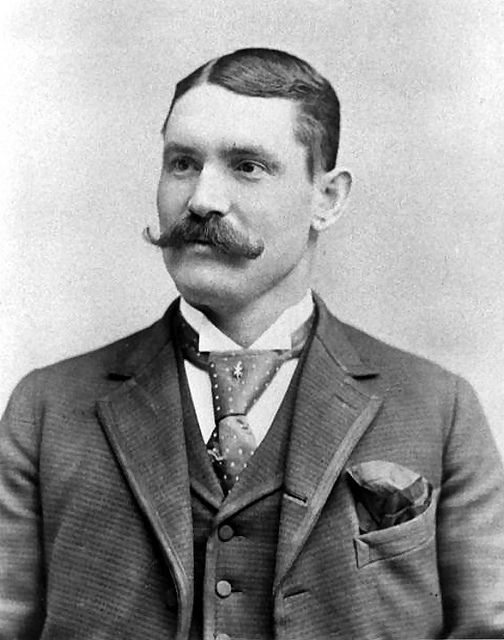

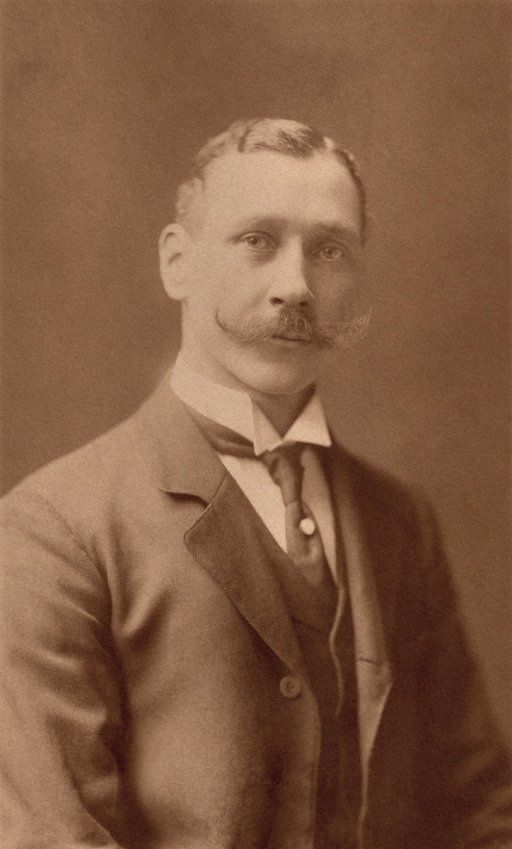

Stickpins were a significant part of fashion history between 1830 and 1920. Cravats, or neck scarves, were very popular at the turn of the 19th century. Wealthy English gentlemen used stickpins to secure the slippery, silky fabrics used for cravats. In the Victorian era, dandy men would accent every outfit with a stickpin at the neck or chest, nestled in the folds of their cravats. Their stickpins were a reflection of wealth, style, and taste.

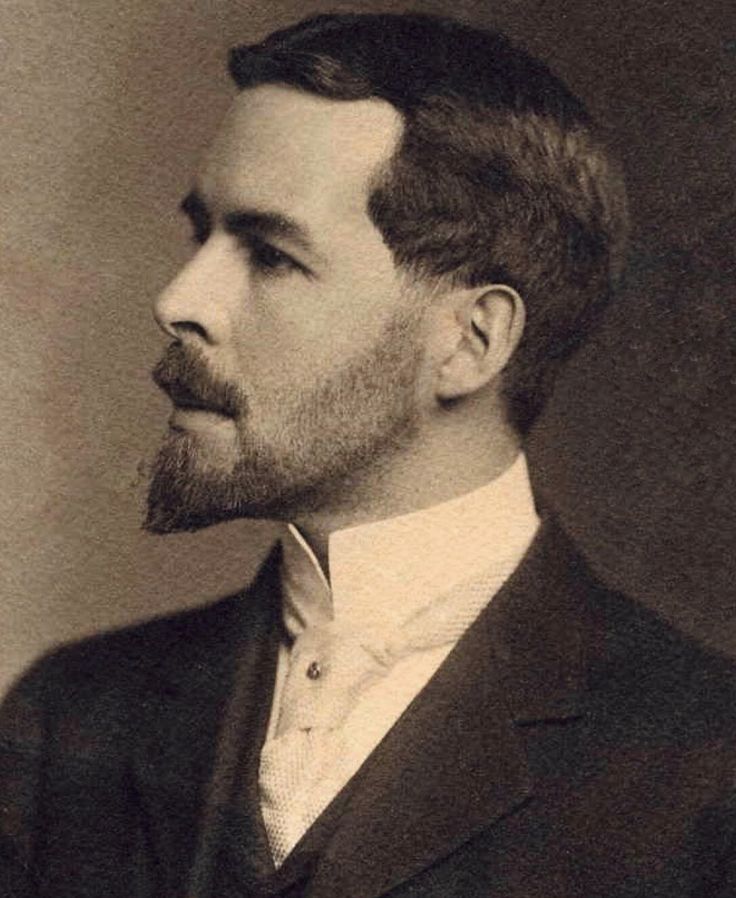

Stickpins began simply as a single gem, pearl, or cameo at the end of a straight pin. At this point in history, the 18th century, there was a surprising amount of labor involved in their creation. They were made by division of labor, which is famously represented in Adam Smith’s 1776 magnum opus Wealth of Nations . Smith used the pin making industry to illustrate the powerful productivity that can occur when tasks are delegated amongst a group, rather than an individual. He observed that a team of 10 could create tens of thousands of pins in a day, but an individual may struggle to complete one. That changed in 1832 when John Ireland Howe, a doctor from Connecticut, received a patent for a stickpin machine.

John Ireland Howe (1793 -1876) was a resident physician at the New York Almshouse when he witnessed the manual process of pin making. Division of labor was used in this case to break down the production into tasks, in which one person would hand their work to the next person to complete the next step of the process. This inspired Howe, who spent 1830-31 experimenting and constructing a machine. He received his first patent in 1832. He initially intended to sell his patent to other companies, but in 1834, he organized Howe Manufacturing Company. In 1836 he set up shop, originally in New York City, and moving to his home state of Connecticut shortly thereafter. Late in 1838, he redeveloped his machine to a new rotary style, that would go on to manufacture for over the next 30 years without need for improvement. This machine was regarded as an industrial marvel by many, best summarized by a quote from an 1839 article:

The apparatus . . . is one of the most ingenious and beautiful pieces of mechanism in the whole circle of the arts. It is impossible for me to give you any adequate description of it. Those who have any fondness for mechanical ingenuity must see it for themselves. Generally, I may state that the wire from which the pins are to be made is passed in at one end of the machine, cut in the requisite length, and passed from point to point, till the pins are headed and fitted for the process of silvering and putting up. The whole process may be distinctly seen, and as one pair of forceps hands the pin along to its neighbour, it is difficult to believe the machine is not an intelligent being.

By 1839, three pin machines were operating, producing a shocking 72,000 pins a day. In 1845, Howe Manufacturing Company employed 30 men and 40 women. They reported producing pins worth a total of $60,000, which translates to over $2.5 million in 2025. At first, these machine made pins were not cheaper than their handmade counterparts, but Howe fought for tariff protection to keep British pins out of the United States. This allowed his business, and other similar American companies, to control the domestic market. Howe retired from the manufacturing business in 1865, and died the following year.

By the 1850s, fashionable and wealthy men began commissioning customized pins as a rare and luxurious form of self expression. More dramatic and exceptional stickpins started to emerge. In the 1860s, machine-made pins were in full swing, and the cravat and stickpin trend was able to be adopted and embraced by the upper middle class. By the 1870s, the motifs used were novel and limitless, a whimsical bit of creativity that could be worn every day. The 1890s is when stickpins finally crossed gender lines and began to be adopted by women, who were similarly delighted by the unique personality of these pieces of jewelry. Active women regularly used them as a part of their sporting costumes, for activities such as horseback riding, boating, tennis, bicycle riding, and golf. Ascots, scarves, and other similar neckwear became popular universally, and none were complete without a stickpin.

This trend continued for two decades, with the industry evolving and creating as quickly as they could to keep up. Many patents were filed for stickpin related innovations. At the turn of the century, many companies started producing stickpins as marketing, giving them away for promotions and gifting them to employees. They were mass produced to be as inexpensive as possible, as they were mostly given away, so many were discarded over the following years. While not valuable in materials, they are interesting pieces of industrial and commercial history and can indeed be quite rare.

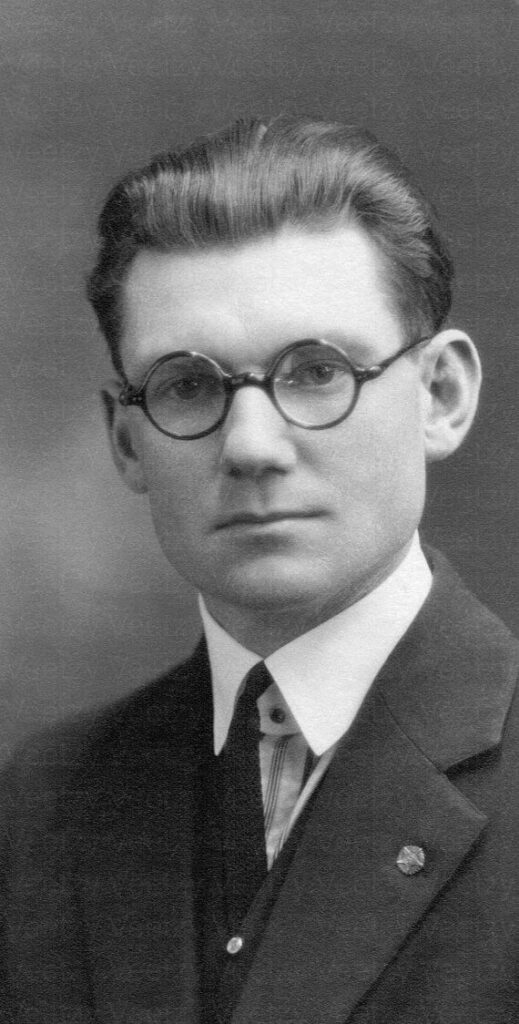

Sharing a fate of many, World War I thwarted the stickpin trend. They continued to be produced and worn into the 1920s, but in much more modest quantities. The popularity of the straight tie led the way to tie bars and tie tacks, which effectively replaced stickpins.

There was a small resurgence in the 1970s, allowing many family heirlooms and treasured antiques to see the light of day once more. Many pins were repurposed or otherwise adulterated at this time, taking many out of circulation in today’s market. This was a relatively quick and mild trend compared to the heyday in the 19th century.

In 1995, Jack and Elynore “Pet” Kerins published a book titled Collecting Antique Stickpins: Identification and Value Guide, which is a singular source of information on collecting stickpins. In it, they document samplings from their collection of 2,500, noting motifs and eras. While it’s difficult to impossible to determine dates or sources of manufacture, they use the following era determinations:

Georgian Era (1714 through 1830)

Victorian Era (1837-1091)

Art Nouveau Era (1890-1918)

Art Deco Era (1920-1935)